The Bahá’í Faith is a monotheistic religion born in the nineteenth century that sees itself as the continuation of the world’s great religions with a new message for the modern age.

Thanks to the world-embracing vision of its founders and the broad appeal of their teachings, the Bahá’í Faith spread around the world in 150 years, becoming a universal movement with several million believers living in every part of the planet and reflecting the diversity of its population.

The Bahá’í Gardens in Haifa and ‘Akko, together with the buildings found in them, represent both the historical memory and the contemporary heart of the worldwide Bahá’í community. Herein lies the “outstanding universal value” that in 2000 was recognized by UNESCO in its decision to add these sites to the list of World Heritage to be preserved for future generations.

The short historical summary below will explain how this all came about and why this story is so significant.

The Báb (Gate) was born as Siyyid ‘Ali-Muhammad in Shiraz, Iran in 1819. As a child, He showed signs of spiritual depth and wisdom beyond His years. At the age of only 24, the Báb announced Himself as a prophet or messenger of God during a period of intense messianic expectations in Iran. He challenged the thinking of His time by forbidding violence and holy war (jihad), recognizing the equality of women, and encouraging science and education. Invoking scriptural prophecy, He claimed to be the Herald come to announce and prepare the way for another Messenger of God who would usher in the age of peace and justice promised in all religions.

After eighteen disciples, including one woman, had independently found their way to Him and accepted His claim, the Báb sent them out to spread His teachings. Within a short time, hundreds of thousands of people from all walks of life, including some well-known religious leaders, were attracted to His message. Feeling threatened by His success, the clergy declared Him a heretic and instigated a wave of persecution during which thousands of His followers were tortured and killed.

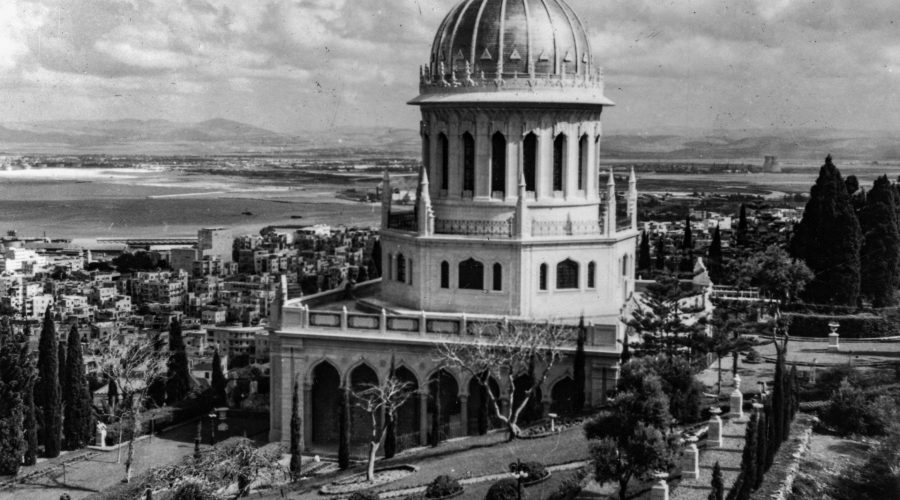

The Báb Himself was confined in isolated fortresses for three years before being executed in a public square in the city of Tabriz, Iran, on 9 July 1850, an event that was witnessed by some ten thousand spectators and reported in the western press. Interrupting a conversation during which He was giving final instructions to one of His followers, guards took the Báb from His cell and suspended Him by ropes against the wall forming one side of the square. Three rows of 250 soldiers each fired in succession, and when the smoke and dust had settled, the Báb was nowhere to be seen. After a frantic search, He was found in His cell, completing his instructions. When He had finished, He calmly announced to the guards that they could now carry out their mission. The first regiment refused to repeat their act, so another one had to be summoned. This time, the bullets reached their target. The Báb’s remains were dumped outside the city and guarded by soldiers to prevent Him from receiving a proper burial. Despite this, His followers succeeded in removing His remains and hiding them in one place after another for fifty years, until they could be brought to the Holy Land and buried in the simple stone structure on Mount Carmel, which was later completed with a monumental superstructure and golden dome. For Bahá’ís, the beauty of the Shrine of the Báb and the lovingly-tended Gardens that surround it are an answer to the suffering and injustices inflicted on Him.

Mirza Hussein Ali (1817-1892), later known as Bahá’u’lláh (Glory of God) was born into a noble family from the Iranian province of Nur. Instead of following in the footsteps of His father, a minister in the royal court, He chose to assist the poor and the sick. When the Báb announced His mission, Bahá’u’lláh became one of His followers and then a major figure in the movement. Like many others, this singled Him out for imprisonment and torture. In His writings, He relates how the announcement of His divine calling came to Him while He was confined in an underground dungeon in August of 1852.

All of Bahá’ú’lláh’s property was confiscated, and He and His family were expelled from their native land in 1853, never to return. The first stage of exile was Baghdad, where Bahá’u’lláh stayed for ten years, two of which were spent wandering alone in the mountains of Kurdistan. Before complying with an order from the Sultan of Turkey summoning Him to Istanbul, Bahá’ú’lláh announced His divine mission to the followers of the Báb, most of whom accepted His claim and became Bahá’ís. After a few months in Istanbul, Bahá’u’lláh was ordered to move on to Edirne in the European part of Turkey. At each stage of His exile, Bahá’u’lláh earned the love and devotion of the people surrounding Him and the jealousy of the clergy and rulers. Finally, in 1868, the Turkish Sultan banished Him to ‘Akko, then a remote outpost of the Ottoman Empire used as a depository for political prisoners and other undesirables. With time, the initial hostility of the authorities and people of ‘Akko changed to respect and affection. After nine years of confinement, first in the citadel and then within the walls of the Old City, Bahá’ú’lláh was allowed to move about freely and to live in the countryside north of the city. The last twelve years of His life were spent in relative comfort in the mansion that stands in the centre of the Bahá’í Gardens in ‘Akko. When He passed away on 29 May 1892, at the age of 75, His remains were buried in a small building next to the mansion, which is known as the “Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh”. This is the place to which Bahá’ís all over the world turn their faces and their thoughts while reciting their daily prayers.

Throughout His life of imprisonment and exile, Bahá’ú’lláh was occupied with the revelation of the sacred texts that came to Him in a constant flow, sometimes with such rapidity that no one could write them down. While still confined within the walls of ‘Akko, He formulated the fundamental laws and principles of His religion in a volume He called the “Most Holy Book” (Kitáb-i-Aqdas). He wrote to the secular and religious rulers of His day, asserting His authority as God’s Messenger, urging them to make peace among themselves and rule over their subjects with justice and compassion, warning them of the consequences of their heedlessness, and in some cases predicting their downfall. In addition to major works addressing theological and mystical subjects, He wrote thousands of letters to individuals in which He explained His teachings and offered personal counsel. In His testament, Bahá’u’lláh appointed His eldest son as His successor and gave him the authority to interpret the teachings and settle differences of opinion so as to protect the community of His followers from dissension and disputes that could lead to schism.